Natural Error

Jacob Sam-La Rose

-

In the 80s, I was a kid with a computer. Born in the late 70s, sure, but for the purpose of these notes, the earliest years don't count. I was fortunate enough to have a teacher for a mother, someone who intuited the importance of contemporary technology, who one day brought something home for me to experiment with. My first personal computer was a Commodore VIC-20. The VIC-20 was supplanted in a matter of years by an Amstrad CPC 464. I would like to be able to state that the exposure to early home computing wired me for visionary prowess in all things technological. Alas, I flirted with BASIC programming for all but a few minutes before discovering what I then determined to be the home computer's true value: gaming. These were the days of tape-based computing. Side-scrolling vistas and 3D isometric graphics. Here, I fully embraced a pixelated, bitmapped aesthetic rendered through a monochromatic green monitor. I lost myself in those game worlds and experiences for hours.

How many people reading this will have any tangible, visceral sense of the kinds of computers the VIC-20 and the CPC 464 were, or the crunchy, warbling whine of code being loaded from magnetic tape into utility? Everything has its span. That world no longer exists in the way it once did.

-

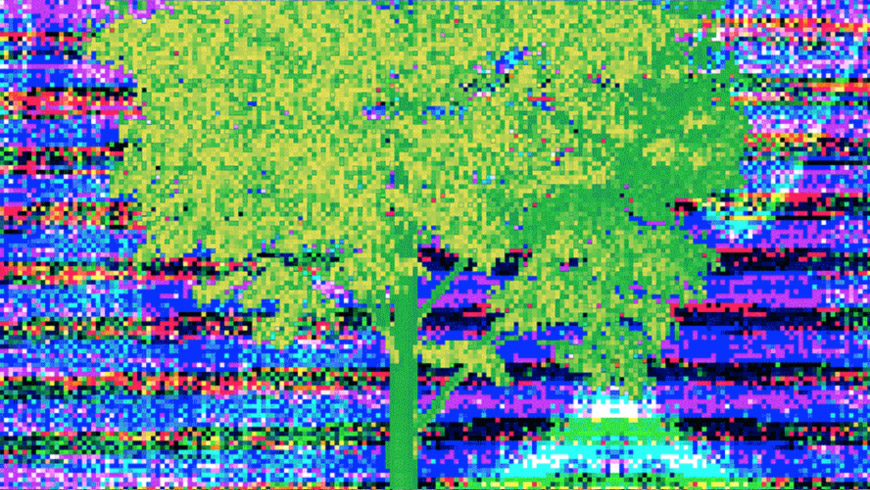

Rodell Warner's Natural Error, one of two commissions in an exhibition considering the impact of climate change on the environment, introduces itself with a riot of colour on the screen. A series of animated portraits of a natural world: eight organisms and a spectrum of conservation statuses. Each animation sits above a scrolling line of ticker tape text, a visual vocabulary that conjures images of news reports and scrolling headlines. No screed, no impassioned essay on the plight and prognosis of the pictured organism, no accusatory finger-pointing, no directly levelled heft of generational guilt. Instead: choice, bullet-pointed details. The mechanics of an eel's movement through water. Conservation status: CRITICALLY ENDANGERED. The Pedunculate oak's sensitivity to mean spring temperature. The delicate nature of the Bristol Whitebeam's reproductive system. There's an intimacy in some of these descriptions. The sky-dancing courtship rituals of the white-tailed eagle. The distinct colour of the large marsh grasshopper's hind inner thigh. The beauty of a conker tree's "showy" flowers. The romance of the Chinese river dolphin's nickname. How to best enjoy eating monkey puzzle tree seeds. Each portrait is an exhibit in itself, an item on display. Pixelated in a way that calls to mind the bitmap era of my youth, set against backgrounds of not-quite-primary but strong and solid colours, constantly shifting, like heat maps, or frenetic meteorological displays ratcheted up in speed. Because, of course, time is of the essence.

-

As I've said, I was a child of the 80s. My memory is marked by some of the key anxieties and calls-to-action of the time— ban the bomb, save the trees, there's a hole in the sky, it's all our fault, and we all need to wake up yesterday. Fast forward to the 2020s, and some of those same songs still ring true. Except perhaps with even more urgency.

-

Warner's portraits and profiles look like treasures. Sacred objects. To my 80s gaming self, each one resembles an item I might have been tasked with collecting in the course of a quest, or the goal of a mission. They rotate in space, as if on virtual pedestals. To be seen from all angles. And they muster a curious tension between movement and stillness, each figure animated and yet frozen in pose. An animated still life capture. Digital taxidermy. A retro-futuristic rendering of cherished mementoes in a display case. Seen this way, they're possessed of a dual nature, the way a memorial simultaneously celebrates a life while lamenting that same life's ending. It's easy to imagine some future child projecting one of these profiled organisms as a three-dimensional holographic light show from a handheld device; as a way to know something of what these living things once were.

-

A Wyoming highway development survey manual defines natural errors as being caused by environmental conditions, or significant changes in environmental conditions.

-

Each animation glitches, as if it were composed of a signal broadcast over a distance, subject to error. They cohere and decohere. Lose bit depth. Dissolve; resolve. The dolphin becomes a simplified crescent arc, an orphaned pixel where its tail once was. Then even that abstract, low-res rendering vanishes. And returns. The ticker tape states that the so-called 'Goddess of the Yangtze' is possibly extinct. A pendulum swings between hope and the likelihood that this dolphin is nothing more than memory. A matter of record. How tenuous the transmissions. How hard to hold each of them in place. To keep them whole. To transmit them faithfully.

-

Famously, the European eel is an avatar for nature's mysteries, a critical symbol of the hubris and limits of human knowledge, the subject of TED Talk articles and viral TikTok videos. I remember an episode of RadioLab in which Robert Krulwich described the way eels feel silky in hand, how it's impossible to touch an eel and not feel wisdom and love. This is the closest I might come to knowing one. The episode went on to detail how, after years of effort and millions of dollars we don't know exactly where or how eels are created (we think somewhere in the Sargasso), despite Aristotle, Pliny, Linnaeus, Freud (yes, Sigmund), Grassi, Schmidt (underwritten by the Carlsberg fortune), Cooke and countless other thinkers, scientists and researchers. My 80s self here wants to build a bridge between these eels and the Amazon. How so much conservation messaging of that time shone a spotlight on deforestation, the unparalleled biodiversity of the rainforest, the trope of natural medicinal compounds and traditional knowledge being de-emphasised and wiped out; how much we've lost before it's even been discovered, with thanks to a human appetite for furniture and cattle.

-

It is in the contradictions between these layers that civilization finds its surest health.

— Stewart Brand -

Not every organism profiled here represents a narrative arc of loss, whether actual or impending; Warner's take on environmental issues isn't all doom or monochromatic shades of the same tragic tones. The white-tailed eagle is a quasi-Lazarus, reintroduced after extinction in the UK. The English oak, although predicted to decline and impacted by shifts in temperature, still carries a conservation status of 'least concern'. Even in the face of species extinction, there is always something to save. But perhaps we'll need to get better at imagining a future. Stewart Brand writes with reference to 'pace layers'— the stratification of different scales of time contained within a single system capable of resilience through persistence, change and unpredictability. Warner's selection of subjects offers a sense of pace layering in itself— from gone-in-a-year-long-flash grasshoppers to the oaks, capable of lifespans reaching 1500 years. How do ecological systems manage and absorb change and shocks? Brand posits that an answer lies “in the relationship between components in a system that have different change-rates.” And this is where Natural Error leaves me: how do we best interrogate our place in time, our relationship with all the other layers (and constituents) within this system? What responsibility do we bear? When faced with Warner's eight and all the countless other organisms that we share a world with, where do we, as humans, fit?

Jacob Sam-La Rose is a poet, editor, artistic director and facilitator. Much of his work is invested in establishing spaces for personal, professional and collaborative growth through poetry, language and creative exchange. His poetry has been translated into Portuguese, Latvian, French and Dutch, and his collection Breaking Silence is an A' level set text. In 2022, Jacob holds the inaugural poetry fellowship for English Heritage and continues to lead the Barbican Young Poets' programme, which he founded in 2009.